Who made Indian Art Modern? Part 2 | Bengal School of Art & Santiniketan

Written by Prapti Mittal

The Bengal School of Art emerged in 1950s Bengal, specifically Kolkata and Santiniketan as an avant garde movement, establishing itself along the lines of the Indian freedom struggle and all its basic elements like Swadeshi movement (self-sufficiency in production), non-cooperation with foreigners, self-governance, unity of all Indians against foreigners, among many others. As a result, artists like Abanindranath Tagore, Benodebehari Mukherjee, Gaganendranath Tagore, Nandlal Bose, Asit Kumar Haldar, M.A.R Chughtai, Bireswar Sen, Debi Prasad Roychoudhury devised new methods of envisioning an independent India that would derive its strength from the rich cultural and historical heritage that it holds and from ideological and metaphysical traditions elsewhere in the world, not being restricted to the European understanding of modernity and progress. Europeans like E.B. Havell who were sensitive to the cause also catalysed the growth of Bengal school of Art by providing them a base to function within the Calcutta school of Art.

Talking in terms of art theory, the paintings of Bengal school of art are characterized by a redefining of historical Indian art styles, especially the Rajput and Mughal miniature art styles. Most artists of this group worked with watercolours, inspired to do so by the Far Eastern brush techniques and calligraphy. Indian Society of Oriental Art produced works that had definite Japanese characteristics, such as the ink and wash, actual lines in the final product, increased use of decorative floral motifs and landscape themes and the human features resembling Japanese features.

There was a very fine line between the Bengal School of Art and the Santiniketan School of Art. Kala Bhavan, the Arts school at Santiniketan established by Rabindranath Tagore in 1901, laid the basis of modern art in India. The school taught music, art and performance art ‘for the coordinated study of the different cultures’ and eventually became the symbol of harmonious coexistence of western and eastern cultures. It was meant to serve as the center for exploration and research into the vast Indian cultural heritage, but one can see influences from all over the world in the member artists’ works. The artists associated with Kala Bhavan were Rabindranath Tagore himself, along with Benode Behari Mukherjee, Abanindranath Tagore, D.P. Roy Choudhury, A.K. Haldar, Nandalal Bose, Kshitindranath Mazumdar and M.A.R. Chugtai. Thus we can see the overlapping and almost similar constitution of the two schools.

One artist of particular importance is Jamini Roy, who did not fit into the descriptions of two schools because of his remarkably distinct artistic style, but who is nevertheless known for the nationalist ideology of glorifying our ancient cultures and traditions. He took pride in the Kalighat paintings and the tribal cultures associated with it. His style had the same features as Kalighat paintings- the big almond eyes, the round faces, broad outlines and tribal themes of festivities and mother-child relationship, but we see that he added his own characteristics to them with bold non-gradated colors and lesser but much bigger figures in one painting.

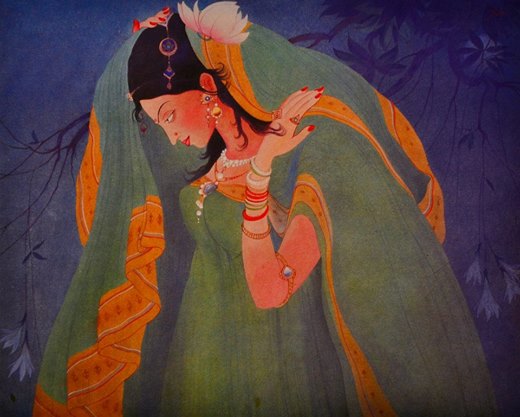

In this endeavor, Abanindranath Tagore was the first major exponent of Indian nationalist values in art. He was the founder of the Bengal school as well the “Indian Society of Oriental Art”. Despite studying the European academic style of painting, he became fascinated with the portrayal of Krishna in the Mughal miniature paintings. He studied Mughal miniatures, Whistler’s aestheticism, Japanese and Chinese calligraphy in his own art, thus making it more spiritual than the ‘materialistic’ art of the West. Around this time, there was a growth of the Theosophy movement in the West, a precursor to the Easternisation or Orientalisation that captivated the West in the twentieth century. His allegorical representation of Bharat Mata (Mother India) is a testimony of both his nationalist alignment as well as the greater ideas of the ideal Bharat that Indians envisioned. The Tagore mansion, in which he grew up, served as a bridge between the white town and the black town (the racial divide in Anglo-Indian cities) and can be spotted in his stories, like Putur Boi, where the imaginary city resembles the colonial city of Kolkata. Though he aligned with the nationalists in his early phase, he soon emerged as a more universal artist, where individualism triumphed over political affiliations. Establishing close relationships with Japanese artists and art critics, he soon formed the “Indian Society of Oriental Art”, looking for an alternative to European modernisation.

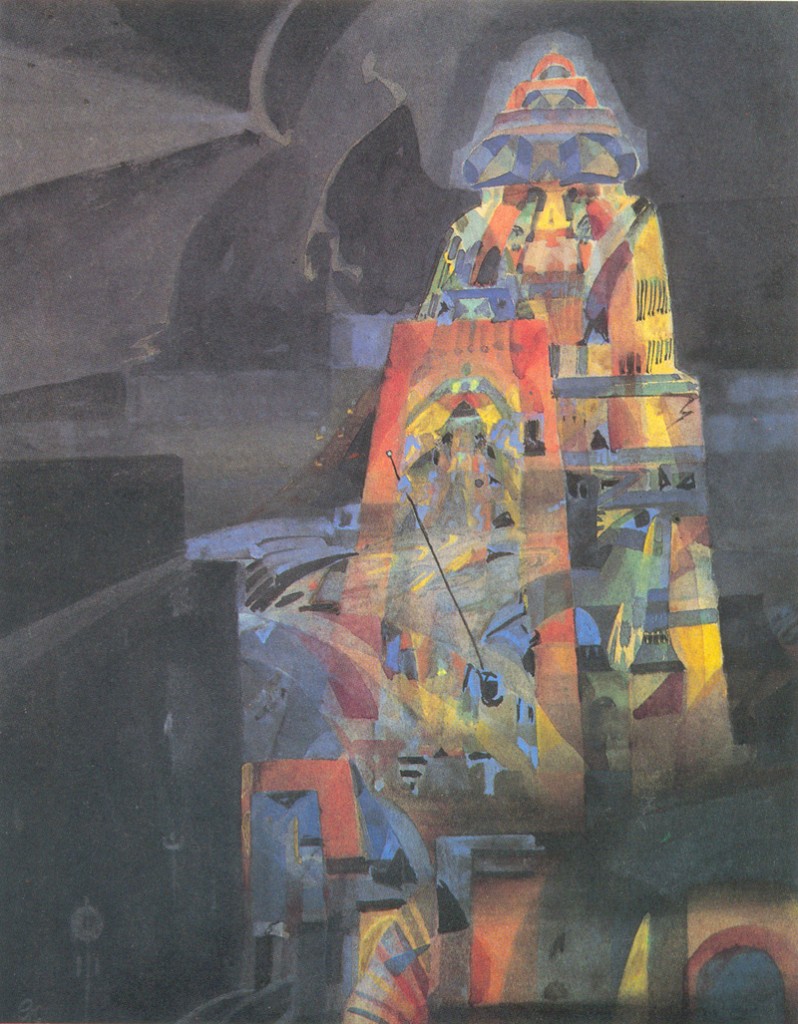

Gaganendranath Tagore was a key member of the Bengal school and the co-founder of Indian Society of Oriental Art. He extensively studied Japanese brush techniques and the influence of Far Eastern art to incorporate into his own work. He primarily worked with watercolours, in a semi-cubist manner, to represent themes in Indian history and cultural-religious practices such as Chaitanya and Pilgrim series. He actively observed politics and soon moved from the revivalist methods of Bengal school to caricatures that were published in many newspapers and later published as a collection.

Asit Haldar is known best for the project of documenting cave art of Ajanta with the objective of bringing ancient Indian art to the wider public. His paintings include Yashoda-Krishna, Kunala and Ashoka, Awakening of Mother India and thirty two paintings of the Buddha, thus embracing idealism in his art. Aspects of Rajput and Pahari miniature paintings find a way into Haldar’s work. The emphasis on detail and precision in technique and the prominence of mythological, historical and literary themes in art can all be found in Haldar’s work.

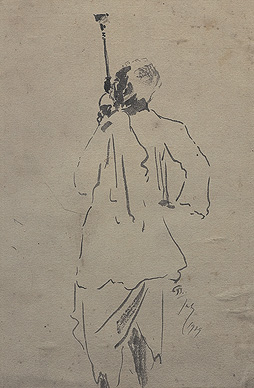

Nandlal Bose was influenced by the Tagore family and the murals of Ajanta and his classic works include paintings of scenes from Indian mythologies, women, and village life. To mark the 1930 occasion of Mahatma Gandhi’s arrest for protesting the British tax on salt, Bose created a black on white linocut print of Gandhi walking with a staff. It became the iconic image for the non-violence movement. He was also famously asked by Jawaharlal Nehru to sketch the emblems for the Government of India’s awards, including the Bharat Ratna and the Padma Shri. Along with his students, Nandalal Bose took up the historic task of beautifying/decorating the original manuscript of the Constitution of India.

Thus, Bengal School of Art became the first cohesive nationalist art group, that did not follow fixed rules of art in matter or technique, rather each followed his own calling in order to gather inspiration from any source to build the modern Indian aesthetic. The common feature in all Bengal school works, however, was the rejection of Western notions of modernity and materialism and embark on a rediscovery of the lost spirituality that was characteristic of ancient India.