Masks of Mexico: A review

Written by Hema Guha

The India International centre in association with the Mexican Embassy, New Delhi had recently organized an exhibition of Masks titled ‘Masks of Mexico’ from 19-31 July 2016. As the title suggests, it was an exhibition of a collection of 33 masks both of the ritual variety as well as the theatrical and folk style.

Carnival Dance mask

One can identify Mexico as a country with a rich and diversified cultural history much like India. We are also familiar with a variety of masks used by performers on the streets to those in the holy precinct corridors of the temples. As such one can identify easily with the masks on display.

More than one hundred ethnic groups existed in Mexico before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. Among them the Olmec, Maya, Zaotec, Mixtec and Aztec gave rise to great civilizations. Masks and costumes were a part of rituals, with the ruling theocrats taking on the characteristics of the gods in their rituals using imitative magic to control the forces of nature and the cosmic struggles. In the 16th century, masks and costumes were widely used in Europe, mainly during carnivals, a festival of pagan origins that had been incorporated into the Christian calendars. The holidays were celebrated with games, dances and entertainment and took place right before the 40 days of lent preceding Good Friday and Easter. Significant military events were also recreated as historical dance dramas using masks.

Mexican dancers can be grouped into different categories according to their content and origin, storylines, characters, wardrobe and masks. Some of the major dance categories in Mexico include propitiatory and cosmic, military-historic, the conquest, Christian evangelization cycle and the elders or hueues. Festive occasions include Carnivals, Easter, the day of the dead, Christmas and Patron Saints celebrations.

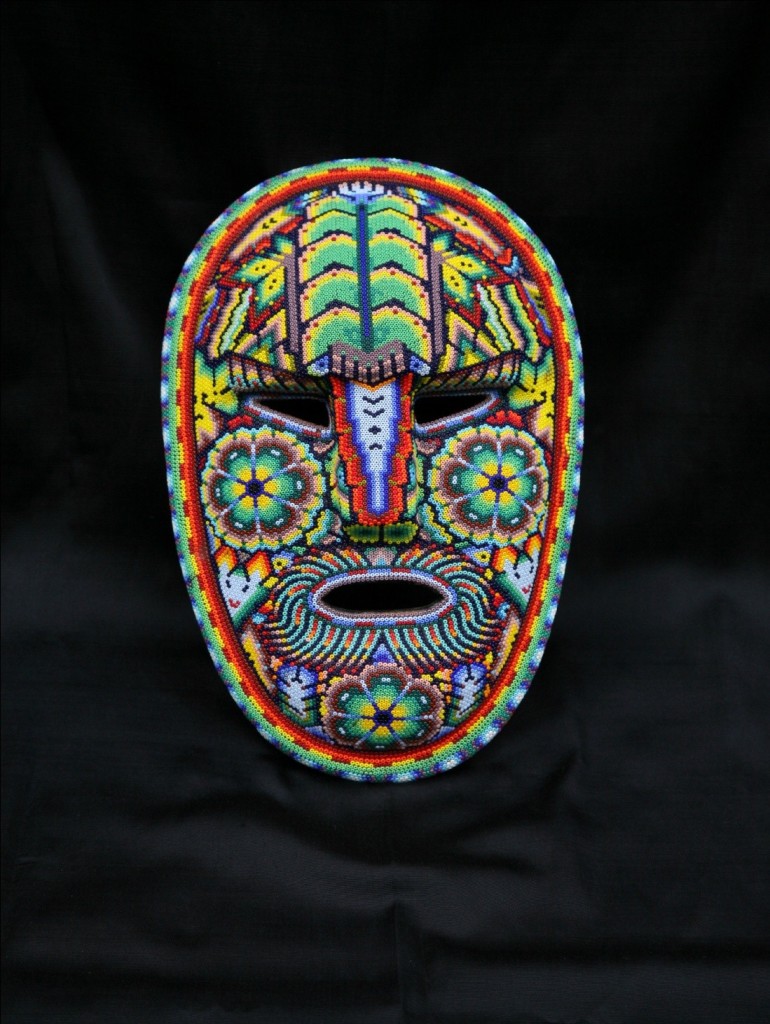

Mask with beads

The masks on display have been made from different materials like polychrome wood, polychrome clay, lacquered wood, bonded paper painted over, masks made with wood and decorated with beads. While themes recur as a result of Mexico’s shared history, it is interesting to see how similar characters are interpreted and portrayed in diverse ways by different culture, community and mask makers.

Neatly displayed on the walls accompanied by a video of various dance forms, the exhibition was a somber yet attractive one. The first one which caught my attention were the Tiger masks from the Tzeltal and Zona de los altos regions .While the tiger mask from the Tzeltal area looks very natural, simple and is made of Polychrome wood and is used by the dancers of ‘Kalala’ ,the other one looks fierce with teeth and hair protruding out. It is made from Lacquered wood, boar’s tusks and hair. As the most sacred animal, the tiger plays a double role in the dance forms, that of evil-where it is hunted and killed-and that of good-when it takes part in the blessing of the land to ensure rain and a good harvest. The bearer of this mask usually wears a jumpsuit with jaguar spots and imitates the feline movements with great ease.

Tiger Mask

The other animal masks on display portray the species which had a significance during pre-hispanic population like the alligator, serpent head, monkey, Iguana, turtle, boar and birds. These masks look interesting but funny. The mask titled fishermen made by local fishermen and used during carnivals is very sturdy as compared to others and is shaped like a fish.

The mask titled Paja worn by dancers during the ‘Pascola dance’ is very different as it is made of palm leaves. The Pascola dance is considered an iconic artistic manifestation of the indigenous groups of Northeastern Mexico. The term Pascola does not only refer to a dance, but also to a set of artistic manifestations that includes music, speech, oral narrative, comedy, textile and wood work. In Mexican traditions, women do not participate with masks in dance. The masked female characters are always played by men dressed up as women, a practice popular in Europe during the 15th century and which has survived till now. The Maringuilla mask on display is from the Purepecha area and made of polychrome wood. With thick eyebrows and eyelashes and red painted lips, it looked feminine, but for the moustaches!

The devil character refers to the process of evangelization and to introduce the concepts of good, bad and punishment. They appear in Christmas, pageant dances, during carnival and the holy week. Covering a broad range of expressions, the devil masks can be playful, almost coquettish, reflecting human traits or his features can reflect the wrath and omnipresence of a hellish expression. The devil mask in the exhibition was from the Uruapan region made of Polychrome wood and looked like a bull with horns painted in yellow and the face in yellow, green and red. The other one was the Devil Tastuan with a red tongue protruding and blue painted horns.

Cora mask

The Cora mask, a fiery one on display has been made with bonded paper with antler bones and painted over in dark pink . It is a ceremonial part used by dancers during Easter and at the end of the performance, the masks are burnt.

The other interesting mask called ‘Wexarika’, are from Huichol region which are wooden masks decorated with beads. These masks look very bright and colourful with the tiny beads arranged on the masks.

Of particular interest are the masks which became popular with the arrival of the African slaves into Mexico, to work primarily in the mines and fields. These masks are able to capture the essence of their salient features and in the dances, they are identified as Negritos. The characters, they play could be serious or they might be a parody.

Dance of the little old men

The masks of old men from the Michoacan region which are used in a traditional dance called ‘Dance of the old men’ are very eye catching with wrinkled features and grinning like old men with few teeth left! It is a humorous dance where the dancers wear masks of old people along with their campesino clothing. They mimic the movements like stooping and coughing of old men.

The Santiago’s mask from Naolinco region made of lacquered wood is used in the dance of the moors and Christians. Interestingly, different pigments and hues of colours have been used correlating with the skin colours of people of various regions.

The Ambassador of Mexico, Ms. Melba Pria says that in Mexico, indigenous cultures have flourished and survived through expressions of popular art and masks are a fundamental element of this magical cultural manifestation. She goes on to add that in Mexico, popular festivities or celebrations allow them to recover their past and incorporate it in intensely in community life today. As rightly mentioned in the accompanying booklet, the masks, separated from their function and purpose, become a work of art, a sculpture of great aesthetic value through which the mask maker unleashes his creativity.